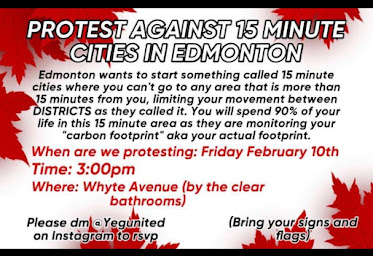

I first wrote about the 15-minute City last year for Senior Line, the Jewish Seniors' Alliance's quarterly magazine. http://gellersworldtravel.blogspot.com/2023/01/the-15-minute-city.html At the time, it never occurred to me that one day citizens would be organizing protests to oppose this widely accepted planning concept. But that's what has been happening in cities around the world. When someone sent me this poster from Edmonton, I just had to write about it again. And while I was at it, I thought I would offer the true meaning of 'missing middle' and 'gentle density' before these terms generated citizens' revolts. Here's my column from today's Vancouver Sun, with thanks to you Mary Beth Roberts for helping to find space for it. I just hope it will encourage a more thoughtful discussion about planning concepts, and encourage colleagues in the development community to consider advertising in West Coast Homes now that the housing market is improving!

I first wrote about the 15-minute City last year for Senior Line, the Jewish Seniors' Alliance's quarterly magazine. http://gellersworldtravel.blogspot.com/2023/01/the-15-minute-city.html At the time, it never occurred to me that one day citizens would be organizing protests to oppose this widely accepted planning concept. But that's what has been happening in cities around the world. When someone sent me this poster from Edmonton, I just had to write about it again. And while I was at it, I thought I would offer the true meaning of 'missing middle' and 'gentle density' before these terms generated citizens' revolts. Here's my column from today's Vancouver Sun, with thanks to you Mary Beth Roberts for helping to find space for it. I just hope it will encourage a more thoughtful discussion about planning concepts, and encourage colleagues in the development community to consider advertising in West Coast Homes now that the housing market is improving!

When my daughter and her cousin get together

to discuss their work at the dinner table, I often have no idea what they are

talking about. Both are doctors, and their conversations are invariably

peppered with technical terms, acronyms and abbreviations that are meaningless

to me.

When my daughter and her cousin get together

to discuss their work at the dinner table, I often have no idea what they are

talking about. Both are doctors, and their conversations are invariably

peppered with technical terms, acronyms and abbreviations that are meaningless

to me.

The same is no doubt true when community

planners discuss whether to ‘relax the site coverage’ or request ‘improved

CPTED measures.’ CPTED (Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design) refers

to building and landscape design features intended to reduce the fear of crime

and opportunities to commit crimes.

Several new terms have been

added to the planner’s lexicon in recent years. Each is attracting considerable

public attention, and one even sparked a widely publicized community protest

in Edmonton. Before they cause more confusion and unrest, it

might be useful to examine what they mean.

‘Missing middle housing’ is one glossary

addition that is often misunderstood, even by planners and politicians. For

some, it is housing targeted to a socio-economic group that is too wealthy to

qualify for government-subsidized ‘social housing’ but too poor to afford

conventional market developments.

However, for most planners, this term refers

to housing forms between conventional single-family detached

housing and apartments. Examples can include duplexes,

triplexes, townhouses and ‘stacked townhouses.’

These housing forms are also referred to as

‘gentle density,’ especially when proposed within established single-family

neighbourhoods. The recent proposals in Vancouver and other cities in British

Columbia to allow up to six homes on a single-family lot are examples of gentle

density.

Allowing laneway or coach houses or the

subdivision of larger houses into multiple suites are other ways to achieve

this gentle density.

Another expression attracting considerable

attention is ‘the 15-minute city.’

First proposed in 2016 by Carlos Moreno, an

associate professor at Sorbonne University Business School in Paris, France, it

refers to an urban planning concept in which most daily activities can be

accomplished by either walking or cycling from one’s home within 15 minutes.

For some, it may include accessing these services and activities by public

transit within a similar timeframe.

The 15-minute city concept gained prominence

when it was used during Mayor Anne Hidalgo’s successful re-election in Paris in

2020. Since then, politicians and planners worldwide have been using it to

describe the types of neighbourhoods they want to promote in their cities or

municipalities.

The key consideration is that the 15-minute city or neighbourhood is quite

different than the auto-oriented car-dependent neighbourhoods that planners

have been creating since the 1950s, where there are no corner stores, and you

often must drive children to school. It may even be necessary to drive to a

neighbourhood park or playground.

If you live in downtown Vancouver, Kitsilano

or Kerrisdale; along Number 3 Road in Richmond or Lonsdale Avenue in North Vancouver;

or in West Vancouver’s Dundarave Village, you already enjoy the attributes of a

15-minute neighbourhood. Indeed, most urban areas built before the overwhelming

proliferation of cars have the qualities of a 15-minute city.

For most of us, this is a very desirable type

of neighbourhood. This is why planners were astonished to learn of a protest in

Edmonton organized by a group opposed to 15-minute cities.

Posters headlined “PROTEST AGAINST 15 MINUTE

CITIES IN EDMONTON” warned residents that “Edmonton wants to start something

called 15 minute cities where you can’t go to any area that is more than 15

minutes from you, limiting your movement between DISTRICTS as they called it.

You will spend 90% of your life in this 15 minute area as they are monitoring

your ‘carbon footprint’ aka your actual footprint. When are we protesting:

Friday February 10th at 3 pm. Bring your signs and flags.”

While conspiracy theorists asserting

clandestine government plans are becoming increasingly common, this had to be

the most remarkable or foolish claim to arrive on my Twitter feed.

To be clear, Edmonton and other cities are not

proposing that residents be confined to a certain geographic area like Patrick

McGoohan in The Prisoner, the 1967 British television series about an unnamed

British intelligence agent imprisoned in a mysterious coastal village.

While many of us enjoy living in 15-minute

cities or neighbourhoods, the challenge for planners and politicians is how

best to transform sprawling car-oriented suburbs into more walkable and

accessible ’15-minute cities’ or neighbourhoods.

Redesigned neighbourhoods will allow residents

to access amenities without having to always get in their cars with the

attendant negative impacts on their health and environment, not to mention

pocketbooks.

One way is to revise zoning bylaws to allow

more widespread mixing of shops and housing. This might include building corner

stores within established single-family neighbourhoods as part of new

townhouses or apartment developments.

It could also include transforming arterial

streets by replacing single-family houses with mixed-use buildings offering

grocery stores, pharmacies and offices with housing above.

Another approach is to add housing, libraries

and even schools on the expansive parking lots surrounding older suburban

shopping centres since, for many of us, the shopping centre is also our

community centre.

Finally, we need to rethink our public transit

system. Instead of having to walk 20 minutes to a bus stop, why not bring the

bus stop to outside our homes? This is already happening with HandiDart and

community shuttle routes operated by minibuses. This will no doubt become more

feasible when autonomous vehicles become more commonplace.

As the expression goes, “everything old is new

again.” This is particularly true when you compare how cities were designed in

the past and how we want them to be designed in the future. With missing middle

housing, gentle density and 15-minute cities, we may all be able to enjoy

healthier lives and healthier cities. Now, this is something worthy of a

community protest.

Michael Geller is a Vancouver-based planner, real estate consultant and retired architect. He serves on the Adjunct Faculty of SFU’s Centre for Sustainable Development and School of Resource and Environmental Management. He writes a regular blog at gellersworldtravel.blogspot.ca and can be found on Twitter@michaelgeller